This article was first published in Scuba Diver AustralAsia magazine, Issue 5, 2008. It appears here in a slightly different form.

You’ve been diving for nearly 60 years now. What still gets you excited about diving? What are your current passions? How have your interests in diving changed over the years? Are there particular themes or subjects you find yourself coming back to again and again?

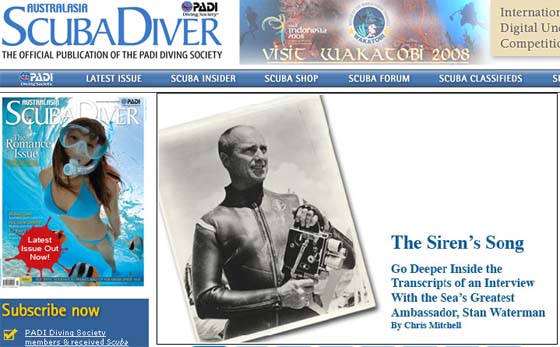

In more than half a century of diving I still find myself compelled by the siren song of the sea. No other venue in my life has provided such an on-going and rewarding challenge. In describing Cleopatra Shakespeare wrote, ” Time can not wither nor custom stale her infinite variety”. I would’t compete with the old bard to express it better than that. Even when I return to dive areas as familiar to me as my back yard – Cayman, Cocos Island, Fiji and the Solomons, that I visit almost every year come to mind – I find new marine animal behavior activities for my video camera and the always fresh physical sensation of committing myself to the ambience of the reef world and the searching adventure of the wall that reaches far beyond my depth.

I am not much given to passions at the age of 85. I do, of course, still have an eye for a well-turned ankle. In the sea my focus has evolved from excitement in working with sharks and big marine animals to the macro world. The H.D. video camera that I now use with the superb optics of today’s housings have enabled me to focus on a seemingly endless discovery of the small life – the macro critters – often bizarre and beautiful – and their behavior. Creating fresh videos for my seminars, film festivals and the entertainment of the guests on the dive tours I host is my business. So I am energized by my work and love what I am doing.

Of course my approach to diving has changed over the years. I went into the sea for the first time so many years ago that I was among the first to seize upon Cousteau’s exciting passport that enabled us terrestial animals to enter a world that had been beyond our reach. Everything was new. We spear-fished like mad. Every dive was accompanied by a sense of adventure and even danger. Then the hunter became a fascinated observer and eventually a conservationist. I like to think that most – if not all – divers followed that course of awareness and care for the new world opened to them.

Roughly how many dives have you made?

I am shamed to admit that I have never kept a log. I have no idea how many dives I have made over the years. I can tell you that it is the professional dive masters on the live-aboard dive boats who, in the long run, accumulate the most dives. As I started writing for dive journals and compounding the material that now forms the text for my first book, “Sea Salt”, I have thoroughly regretted the lack of a dive log. A dive log could have recalled the many details that should accompany an account of adventures in the sea long ago.

You bought one of the original aqualungs back in 1951. Did you ever have any contact with Cousteau?

I still have a summer home in Maine. My first use of the AquaLung was in front of my house on Penobscot Bay. That was about 1949. I supplemented my income as a blueberry farmer with small marine recovery jobs. I had the only SCUBA equipment in the area, possibly in the State of Maine. My little compressor, made by Cornelius, was #25. My insulation was a latex back-entry suit under which I wore long underwear. It leaked. I froze; but I was young with a good metabolism and could handle it. I do not dive in Maine any more, having – long since – become spoiled by warm tropical waters all over the ocean world. I work in my woods, read on my porch that looks out on the sea, eat lobsters that I buy from the lobsterman right in front of the house and leave that cold water to younger divers.

I never knew Cousteau well. We were on many programs together over the years and knew one another, but I never dove with him. His younger son, Philippe, was a good friend. Our families visited back and forth. He died some years ago in a plane crash. His successor, Jean Michel, is also a friend. We meet too seldom. I think highly of him and very much commend the fine work he is doing in promoting marine conservation and sustaining the reputation of the Cousteau name. He is a superb communicator with a splendid sense of humor. I wish circumstances enabled us to meet more often.

Jacque Cousteau is for the diving world the man of the century. Hans Hass actually pioneered diving and underwater camera use before Cousteau, but Cousteau’s co-invention of the AquaLung, and especially his charisma, enterprise and showmanship in publicizing his expeditions into the sea awakened the world to an entirely new era of diving. His first television series was a master stroke of showmanship.

You lived the dream of quitting your job as a blueberry farmer and moving your family to the Bahamas to set up a dive operation. It ‘s a very romantic notion – but did it feel romantic at the time or was it hard work to make such a huge change to your life?

In 1953, when we were living in Maine, I came across an article by Cousteau in “National Geographic” magazine. That was the genesis – the first spark – of a wild new thought. Perhaps, by taking a chance, I could project myself into a new and exciting world of adventure in the sea. The life Cousteau had carved for himself was wonderfully appealing. Quite frankly blueberry farming was circumscribed by long periods of inactivity. It was also economically precarious and hardly inspiring as an activity. What did it take to change the course of my life? The answer soon dominated my mind. Take a chance; make a move. In Conrad’s “Lord Jim” I had read, “To the destructive element submit yourself, and by the exertion of your hands and your feet in the water, make the deep, deep sea hold you up”. That somewhat obtuse but literary exhortation by the master writer was none-the-less inspiring for this young, restless farmer. It led to the building of a boat with a Maine Coast lobsterman hull and specially designed for diving. Contacts were made with friends in the Bahamas. In 1954 I took my new boat, Zingaro, all the way from Maine to Nassau and, with the help of my friends there, set up business as a diver with a small live-aboard dive boat capacity. The family moved with me. The children started school there and I gradually developed a clientele.

Did you ever think you would fail and have to go back to the “real world”? Was it a struggle in the early years to look after your family and pursue your love of diving?

It was hard work. There was resistance from the local charter boatmen. The economics during my three years of seasonal charter-boat diving were not really viable. But a start was made. That was the beginning. I studied with Robert Frost when I was at Dartmouth College. He wrote about encountering two roads that diverged in the woods he was traveling: “Oh, I held the first for another day, yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted that I should ever turn back”.

I sold my boat and broadened by reach by working with expeditions on others’ boats. Ultimately. and with the coming of television, my experience with a camera under water enabled me to earn a viable living by contract shooting for various networks and especially the ABC American Sportsman Show. My book chronicles the years of lecturing across the U.S. with my documentary movies and moving on to the television years.

You’ve often said sharks are “box office”. You’ve made numerous award-winning shark programs. Do you still love diving with sharks?

I like to say that sharks put my children through college. The public has long had a love/fear relationship with sharks. The response to entertainment focused on the so-called “Maneaters” has been – and so continues to be – virtually insatiable. Consequently I was much of the time contracted to work with sharks or with other “dangerous” marine animals. Peter Benchley, the author of “Jaws” moved to Princeton, NJ, became a neighbor and ultimately my best friend. We worked together on dozens of shows for ABC, ESPN, CBS and the Discovery Channel. I shared the underwater shooting for the epic documentary, theater-release movie, “Blue Water, White Death” with Peter Gimbel (the Producer) and Ron Taylor. Ron and his wife, Valerie were – and still are – Australia’s most famous diving team. From the seminal experience of filming oceanic white tip sharks in open ocean off South Africa we began to “push the envelope” in learning how we could work with sharks. I have written much about that benchmark experience. It was frightening. We did not know if we could get away with it, but we did. For Ron and me, both of us seriously earning our bread by working with cameras underwater, it was a fortuitous start of a lifetime of shark experiences. That first risky trial was not entirely insane. It was a calculated risk that paid off. Than again, perhaps it was a little insane. Remember, it was the wise Zorba who maintained, “A man needs a little madness or he never breaks the rope and goes free”.

In the last two years of his life Peter devoted his writing and speaking engagements to the need for conservation in today’s very troubled ocean environment. His last book, “Shark Trouble”. is dedicated to that end. Of course he focused most specially on the alarming degree to which overfishing has critically diminished the population of sharks.

Many species are now seriously endangered. Sharks as an “apex” predator are as essential to the critical food chain at the very top as the mass of microscopic and zooplankton are at the base. The latter are mortally vulnerable to the planet’s warming climate. The sharks, at the top of the food chain. are equally vulnerable to the overfishing. In short, technology has so increased our ability to make enormous catches (i.e. with fifty-mile long lines, deadly gill nets, draggers and multi-million $$ purse seiners) that the harvest has already long exceeded the ability of the catch to reproduce. Sharks, especially, with their long gestation period and small reproduction are in alarming retreat. Shark finning, only recently coming into world view, is the most egregious. irresponsible practice today. The disgraceful waste of the whole valuable animal is appalling. The bodies are dumped alive after the fins have been removed. The continued market for the making of a ceremonial soup still favored in the parts of Asia and the Orient, is so shocking and retrograde to all tenets intelligent conservation and environmental thinking that I find it beyond the pale. One man’s soup may be another man’s enigma. Any way one may look at the long view of it, time is running out for the shark.

An essay, ready for my next book, is entitled, “Pushing the Envelope”. I write about some of the wild levels of rapport divers are testing with sharks these days. I recently edited a short documentary on a Fijian diver friend who has, for the past three years, been hand-feeding a 16-foot tiger shark named “Scarface”. The animal is as docile as a puppy. The video is hugely successful because it is sensational. Shooting the action was not a “Dare Devil” activity. Because my friend, Russi, had long established the rapport with the great animal I sensed no risk in filming the scene. My dive companion and business manager, Nancy McGee, actually shot so close behind Russi that Scarface several times collided with her camera. Hundreds of thousands of sport divers have witnessed the hand-feeding of sharks by dive guides all over the diving world. I have never been one to try those antics for the first time. The experience off South Africa back in ’68 was the exception. While the documenting of those spectacular activities is good business for the videographer I none-the-less question the veracity of it all. Are we demeaning the great predators by demonstrating to the public that “man, brave man” can reduce them to lap dogs?

One of my essays in “Sea Salt” is entitled, “The Rambo Out-Of-the-Cage Club”. Those demonstrations of daring can engender in the viewers a notion that the ancient predator is defanged and no longer dangerous? Just one mistake in the conditioned routine of the feeding and the primordial instincts of the great animals can instantly switch to an attack mode. I have in my archival collection of rare underwater takes a graphic account of just such an occurrence. Some years ago an old friend, Dinah Halstead, was demonstrating the hand-feeding of big silver tip sharks to guests on a dive tour off the eastern side of New Guinea. The demonstration was a regular event having been successfully performed many times. This time the routine varied by one seemingly innocuous change. Dinah had repaired the holes in the knees of her wet suit with white patches. One of the guests was recording the scene with his Hi-8 video camera. As the seven-foot silver tip approached to take the fish bait from her extended hand the flash of the white knee cover caught its eye. The jaws opened and took the knee instead, closing over the thigh above the knee and the calf below. All seven feet turned in a split second for a second bite. By instinct Dinah also turned and thrust the Nikonos and strobe she was holding in the other hand into the gaping mouth of the shark. The animal turned away away with the camera in its mouth, its head shaking convulsively. It turned in a wider arc and was repelled by Dinah’s husband, Bob, who diverted the next attack with the shark billy he carried. The speed of the action – the incredible speed of the shark’s turn – is perhaps the most shocking part of the scene. The long prevailing notion that one may just punch an attacking shark on the nose, or dexterously doge aside, go out the window. The videographer generously gave me a copy of the video. I use it as a post script to a video I produced about three different versions of shark feeding then popular in the Bahamas. It is a very effective and educational counter to the impression left with thousands of divers who have watched the performance of docile, “friendly” sharks at the shark-feeding activities. Over three hundred million years of survival and evolution the instincts of the great ocean predators have not been erased.

You’ve influenced and encouraged scores of photographers and videographers over the years. Did you have any role models when you were starting out with filming? Do you think it was easier back then to make a name for yourself because so few people were doing underwater filming? And are there any filmmakers today that you particularly admire?

For me it was a matter of serendipity that I was born into an era during which man was given the tools to move into the sea. I had a modest economic legacy from my father. It enabled me to “take a chance”, indulge a capacity for adventure and realize a dream that made my “……vocation my avocation, as my two eyes make one in sight” (again Frost). By having been carried into the new and exciting activity and stayed with it I have been generously awarded by the industry. The medals, plaques, accolades and the like are gratifying. I hope that my ego is normal in that regard. Just by staying the course for so long without making too many mistakes and doing a workmanlike job the awards come your way. Having five Emmies sounds great and is impressive in one’s bio. Did you know that the recipient has to buy the Emmy statue? All of mine were automatically won by just being a part of the crew for a television program that won an Emmy in the “Sports Division”. That, at a higher level, might very well have had a political base.

A new and young cadre of underwater cameraman and producers far exceed my own skill and accomplishments in those early years. In my own country, the USA, I consider Howard Hall as fine a cameraman as one may find. He and his wife, Michele. produce the splendid IMAX productions about the sea and diving that we have today. Adam Ravitch, a young scholarship winner who worked with me years ago recently shot and produced for National Geographic a stunningly beautiful video on polar bears and walruses in the Arctic Circle. Also for National Geographic Nick Colyonos, over a period of two years, shot and produced the finest documentary on the life of the New England lobster. He endured the hostile, cold and murky waters, the habitat for that delicious crustacean, during all the seasons of the year. The cameramen who contributed to the British series, “Blue Planet” are tops in their craft. Old timers like Chuck Nicklin and Al Giddings (now retired) far outreached me in production skill over the years. Many in Europe and Japan have reached levels of skill that I could never have aspired to. Leonardo Blanco, a commercial pilot in Spain, is one of the finest shooters and editors of his own video that I have encountered. It is a brave new world of diving cameramen and ladies with a grasp and use of technology that is beyond me. It was definitely easier for me to get jobs and be paid well by being ready with experience long ago when there were few competitors in the field.

I had no part in the production of “Jaws” but did work with Peter as one of three cameramen for the shooting of “The Deep”. Al Giddings and Chuck shared those credits with me. I had so much fun working on the ABC American Sportsman shows with Peter that I am unable to pick a single one that was most special . I believe we did 12-14 of those shows over the years.

I attend three major film festivals every year. “Our World Underwater” is in Chicago. The Boston Sea Rovers Annual is in Boston and “Beneath the Sea” is conducted at the Meadowlands across the river from New York. At those gatherings I watch with pleasure the work of the top film makers, present my own videos at seminars and catch up with many old friends. Occasionally I am asked to host the evening film festivals and enjoy doing that. However, being long of tooth and well advanced into the vale of years I occasionally forget the name of the person I am supposed to be introducing. Audiences are invariably tolerant. A sense of humor is essential.

You’re famed for derring-do adventures underwater, but you also read English at university with Robert Frost. Did you learn anything in particular from him that helped you in later life? Is there an intellectual or spiritual edge to diving for you?

I do reflect on my life at times, especially when I am sitting in my favorite chair and reading by the fire in the evenings. My wife, Susy, and I share those evenings with regularity when I am home. We always have a wood fire until the weather is too warm for it. Wood fires are great for reflection. That is when I think of the adventure years, the many experiences that have composed a major fabric of my life and the substance that made writing a book possible. I am pleased and also grateful for having taken that chance long ago. Should I be eaten by a shark tomorrow or slip on a banana peel and go to that great SCUBA Diver in the sky, I will go very well satisfied with my portion of life experiences. They fulfill Robert Frost’s philosophy on life. He wrote: “But yield to their seperation, my object in living is to make my vocation my avocation, as my two eyes make one in sight. Only where love and need are one and the work is play for mortal stakes is the deed ever done for Heaven and the future’s sake.”

Stan’s own official website has unfortunately gone offline, but it’s archived from 2015 at Archive.org